Citylab — "Buildings Don't Have To Be Bird-Killers"

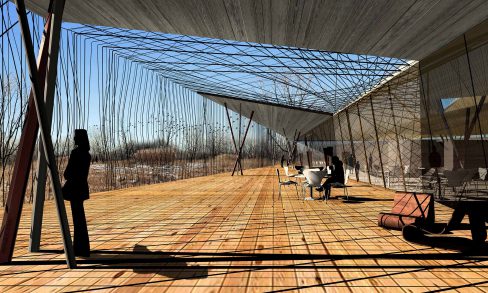

‘North America’s most-trafficked migration route is the Mississippi Flyway, funneling birds from across the Canadian interior, down the path of the river and out into the Caribbean. Chicago and Lake Michigan are prime stopover points on the route south. In 2003, architect Jeanne Gang (another MacArthur winner) was working on the competition for the (unbuilt) Ford Calumet Environmental Center in Big Marsh Park on Chicago’s South Side. The center’s swampy industrial setting turned out to be part of the Mississippi Flyway. “It was called Best Nest, because we were building it similar to a nest, using things that were abundant and nearby,” she says.

Following the Ford Calumet design, Gang had an epiphany much like mine at Brooklyn Bridge Park, and became a birder herself. She has toyed with the idea of developing bird-friendly industrial products, including undertaking at-home experiments. “When design architects propose a mirror building in a landscape, it boggles my mind,” Gang says, extending her advocacy to an op-ed, published in 2020, calling for Chicago zoning changes closer to those adopted by New York City at the start of this year.

Glass corners, for example, can be especially deadly to birds because they think they can fly straight through. “But if you put a bird feeder very close to a glass-on-glass corner, birds see it and go toward it,” slowing before they hit the surface. “That’s something a homeowner could do on a problematic corner.”

It’s fun to think of a skyscraper architect like Gang experimenting at home with bird feeders. In fact, the two settings aren’t so far apart. The lowest 50 feet of a building are within the scope of building owners both large and small. Homes and low-rise buildings account for 99% of all bird collisions, according to a 2014 study by researchers at Oklahoma State University, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Smithsonian Institution’s National Zoo.’